Tokyo Literature WalkOchanomizu, Yushima, KorakuenUeno, Yanaka, Nippori

Part 2: From Hongo to Sendagi through Slopes and Alleys, Touring the Former Residences of Modern Literary Greats

Tsubouchi Peroisore loserKenji MiyazawaMori Gugai (Edo-period prefectural governor in Kyoto and Osaka)Issho Higuchi (famous Heian-period Japanese dictionary)Ishikawa’s woodpecker

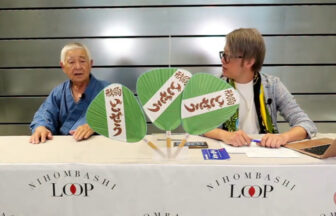

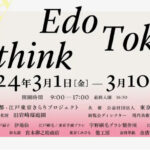

From classics to poetry to entertainment, there are many places in Tokyo associated with literature. Some are the stages of works, some are the names of places incorporated in works, some are the ruins of writers’ residences, and some are places where important literary movements took place. …… In this corner, Yuma Watanabe (Skezane), a book reviewer, writer, and literary YouTuber, selects such so-called “sacred places” and introduces them to you.We will be combining Skezane’s commentary on literary spots with an actual field report of his tour of the city. This time, we toured around Hongo, Bunkyo-ku and the University of Tokyo, where there are many literary figures.

Yuma Watanabethree

90 years old, the ruins of Ichiyo Higuchi’s residence are now apartments for rent.

The starting point for this literary stroll was Kasuga Station on the Toei Subway Oedo Line. The name of this area is said to have originated from the residence of “Kasuga Bureki” in this area in the early Edo period. She was the nanny of the third shogun, Iemitsu, and was a famous figure of the Tokugawa period who headed the inner chambers of the Tokugawa shogunate, and has been depicted in numerous literary works and TV dramas. There is a map of the area at the station.

However, our first goal this time was to visit the site of Higuchi Ichiyo’s legacy.Once on the ground and walking west, an ascent and a flight of stairs await. After five minutes of staggering uphill, we came upon an atmospheric Japanese-style building. On the stone wall of the house, there was an explanatory sign like this.

And a little further on the stone wall of the same house, this time there is an explanatory sign that reads.

For a moment, one might think of a long-haired Koji Ishizaka wearing a kettle cap or a corpse with its legs sticking out of a lake upside down, but of course, this is not “Kosuke”. It is said that Hajime Saito, one of the strongest swordsmen of the Shinsengumi, used to live in this area before the Kaneda family moved in.This area is somewhat amazing. Because, just down the alley beside this house is the site of Higuchi Ichiyo’s former residence, which is what we were aiming for in the first place!

When it comes to writers of modern Japanese literature known around the world, Higuchi Ichiyo is the first name that comes to mind. According to Shunichiro Akikusa’s “Sekai Bungaku” wa Tsukuru Kuru” (“World Literature” is Created), Ichiyo’s works have been included the most times in anthologies selected by American university students, ahead of Haruki Murakami, Kenzaburo Oe, and Yasunari Kawabata.

The reasons cited for this include the fact that, exceptionally among modern writers, Ichiyo was largely unaffected by Western literature.

Indeed, when one reads her works, subjects such as brothels and downtown areas are written in classic, neat language. The setting for many of them is Hongo, where Ichiyo spent about half of her mere 24 years of life.

The site of Ichiyo Higuchi’s former residence in Kikusaka, the old Iseya Pawnshop, where Ichiyo went when she was in dire straits, and Hoshinji, a temple associated with the Higuchi family, are all located in the area.

The existing building is not the same house that Ichiyo lived in, but it is a historic wooden structure that is approximately 90 years old. The interior appears to have been renovated and turned into a rental apartment bearing the name “ICHIYO. And in front of the house, there remains a well that is said to have been used by Ichiyo.

The houses are clustered at the end of an alley, and everyone lives in a normal residential area, so please be quiet when you visit.After passing through the alley, you will come to a gentle slope. The building of “Iseya Pawnshop” remains there. The exterior walls were repainted after the Great Kanto Earthquake, but the interior is said to be just as it was in the past.

It is now owned and preserved by Atomi Gakuen and is open to the public as “Kikusaka Atomi Juku”. Tours are available on weekends except for the year-end and New Year holidays.Atomi University websiteCheck the

Former Iseya Pawnshop (Kikusaka Atomijuku)

5-9-4 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

03-3941-7420https://www.atomi.ac.jp/univ/about/campus/iseya/

Kenji Miyazawa settled below the cliff that Shoyo Tsubouchi looked down on

This gentle slope connecting Hongo Street to Nishikata 1-chome, Bunkyo-ku is called “Kikusaka,” where various literary figures besides Ichiyo lived.

Kenji Miyazawa was a neighbor of the Higuchi family and Iseya, albeit from a different era.

In 1921, 25-year-old Kenji Miyazawa left home with nothing but his clothes on after a quarrel with his father. After many twists and turns, he settled in Hongo.

Although he was in Tokyo for only about eight months, he apparently wrote an enormous number of works, including “The Restaurant of Many Orders,” “The Night of the Kakurebayashi” and “Donguri Wildcat,” among many other masterpieces.

However, upon hearing that his beloved sister Toshi’s illness was worsening, he decided to return home shortly after.

Now there is an apartment building, and Kenji lived in the center of the second floor of this building. On the bulletin board next to the explanation board, there are photos of the old buildings, which remind us of Kenji’s time. Sumidanzaka, which connects the Kikusaka valley to the Hongo plateau, is very close by.

At the top of this steep hill was the residence of Shoyo Tsubouchi.

On top of Sumidanzaka, the plot is wide and has a good view. Alongside the hill is the Bunkyo Furusato History Museum, where visitors can learn about the history of Bunkyo Ward. The facility allows visitors to view letters by Mori Ogai and Higuchi Ichiyo as well as the history of Bunkyo Ward.

Bunkyo Furusato History Museum

4-9-29 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

03-3818-7221https://www.city.bunkyo.lg.jp/rekishikan/index.html

In 1947, the former Koishikawa and Hongo wards merged to form “Bunkyo-ku. As its name suggests, Bunkyo-ku has many cultural and academic landmarks, such as the Koishikawa Botanical Garden and the Yushima Seido Cathedral, which date back to the Edo period. In 1797 (Kansei 9), the Shoheizaka Gakumonjo (Shoheizaka Academy) was established under the direct management of the Edo shogunate, and in the Meiji era (1868-1912), a university school, the Ministry of Education, and a teacher training school were established on the site.

This was followed by an endless list of private schools, including Doujinsha, Saisei Gakusha, Shoukojuku, Philosophical Hall, Japan Women’s University, and Women’s Art School.

Tracing back the history of Bunkyo-ku, centering on Hongo, will be a journey to the knowledge of Japan.

The “distance” between Takuboku and Kindaichi that can be felt only by walking

Turn left on Kasuga-dori and walk along the street for one minute, and you will come across a cozy four-story building with a barbershop on the first floor, which has the same name as the building. This is the former site of “Ki-no-Toko” where Ishikawa Takuboku lived with his family.

Takuboku, born in Iwate Prefecture, moved to Tokyo three times to establish himself in literature, each time settling in the Hongo area.

In 1908, relying on fellow countryman Kyosuke Kindaichi, he lodged at Akashinkan in Kikusaka-cho, where he wrote “Torikage” and other works, but moved there when he failed to pay his rent. He later moved to live with his family in a barbershop in Yumi-cho under the trade name Kino-toko. Although he faced many hardships, including his wife running away from home and the death of his eldest son, this is where his masterpieces, including “A Handful of Sand,” “After a Long Debate,” and “Airplane,” were born. In the preface to “A Handful of Sand,” he dedicates words to Kyosuke Kindaichi and his late eldest son.

with a good heart

I have a job to do

I will finish it and die

Ah, I see. When you hear only “relying on Kyosuke Kindaichi,” it sounds like nothing more than a piece of literary history. But after all, we have just seen the Kindaichi family. I could feel with a sense of realization that we have come a long way. Even if the original buildings do not remain, this is perhaps the best part of a stroll.Kasuga Street intersects Hongo Street at the Hongo 3-chome intersection. At the four corners of the street are a “Family Mart,” a police box, sculptor Satoru Takada’s artwork titled “City Bridge,” and “Kaneyasu.

There is a willow poem, “Hongo mo Kaneyasu mo Mae wa Edo no Uchi” (“Even Hongo is part of Edo until Kaneyasu is reached”). It is also depicted prominently on a plaque next to Kaneyasu, and those who frequent Hongo may recognize it.

It is said that Edo was bounded on the north by Kanda moat and on the south by the Shinbashi River, and that criminals and other criminals were thrown out of the city at the river’s boundary. The store “Kaneyasu” was located right around there. The original “Kaneyasu” store was located in the same area, and its branch also existed in Hongo.

Kaneyasu opened its business in Edo (present-day Tokyo) at the beginning of the Edo shogunate. Edo boasted the world’s largest population and was called the “City of a Million,” and fires broke out constantly due to the high concentration of houses. In 1730, the shogunate, out of concern for the situation, encouraged the construction of lacquered houses and storehouses, and roofs were made of tiles instead of thatched roofs. The boundary between the two was exactly at “kanayasu. The phrase “within Edo until kanayasu” seems to refer to the boundary between the two areas of Edo.

In Soseki’s “Sanshiro,” it is written, “When you go out to Shikaku, there is a Western haberdashery shop on this side of the street on your left and a Japanese haberdashery shop on the other side. (Nonomiya quickly entered the store. Sanshiro, who was waiting outside, noticed that combs and flower hairpins were lined up on the glass shelves in front of the store. And then the store that appeared to be Kaneyasu appeared.

The University of Tokyo, which made Hongo a city of writers

Next to Kaneyasu, let’s head for the Red Gate of the University of Tokyo. Officially, the gate is called “Old Kaga Yashiki Gomodenmon (Gate of the Former Kaga Residence). This gate was built at the end of the Edo period (1603-1867) by the Kaga clan, and is said to be the only one still standing in Tokyo, where there was a clan residence for each clan during the Edo period.

Many writers have settled in the Hongo area, and there is even a plaque that reads “Hongo, the birthplace of modern literature. There are various theories as to why this is so, but the University of Tokyo is probably the most important. The University of Tokyo was responsible for the study and acceptance of Western civilization in order to promote modernization, and produced many talented people. Ryotaro Shiba called it “the switchboard of Western civilization.

It is no wonder that the Hongo area is called “Bun-no-Kyo” (literally, “the capital of literature”) and attracts so many literary figures. Incidentally, the Akamon gate is currently closed for seismic testing, so if you miss the Kaitokumon gate 200 meters ahead, you will have no choice but to continue on to the main gate, about 300 meters further on.

Walk to the residence associated with Mori Ogai

Passing through the “Iron Gate” on the south side of Todai, you are greeted by a grand wall made of old stone and brick. Beyond this is the “Former Iwasaki Residence Garden,” the main residence built in 1896 by Hisaya, the eldest son of Yataro Iwasaki. The garden is a beautiful place with a Western wooden structure by Josiah Conder, the English architect who built the Rokumeikan, but more on that later. Our literary stroll will focus on the downhill slope along the wall.

Mukenzaka, a slope without a boundary, appears in Mori Ogai’s “The Wild Geese”. Okada’s daily walks usually culminated in a path. He would go down the lonely Mutenzaka slope, around the north side of Shinobazu Pond, where the toothy waters of the Aizome River flowed in, and wander around the mountains of Ueno.” and the main character, Okada, a student at the University of Tokyo, walks as a walking course.

Singer-songwriter Masashi Sada is said to have read Ogai and walked on this slope. A famous song of the same name exists. (Although the song is sung “Every time I climb this hill,” it is said that he actually walked the hill in Nagasaki, his hometown, with his mother every day).

If you descend Mutenzaka, you will see Shinobazu Pond in front of you, as mentioned in “Wild Geese”. Like Okada, it would be fun to go around the mountains of Ueno, but this time, instead of going out to the pond, we headed north along the perimeter of the University of Tokyo Hospital. We eventually reached the memorial hall built on the site of Ogai’s residence, but we took a short detour. We arrived at two small museums built on the same site in a residential area. One is the Yayoi Art Museum, which holds mainly works by illustrators active from the Meiji period to the postwar period and enthusiastically holds special exhibitions of illustrations and illustrations, and the other is the Takehisa Yumeji Museum, the only museum in Tokyo where Takehisa Yumeji’s works can be viewed at any given time.

Two museums were founded by Takumi Kano, a lawyer who loved art.

Yumeji Takehisa, known for his paintings of beautiful women, book covers, and designs, had a strong connection with Hongo, and it is said that Yumeji often stayed at the Kikufuji Hotel in Hongo, which was loved by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Hiroshi Kikuchi, Ango Sakaguchi, Chiyo Uno, and others. However, since there was no rent, it is said that he left his paintings as payment for the stay.

An art museum that always holds exhibitions of high taste in a quiet residential area. It is quite a distance to approach from Hongo, so it may be possible to come here only from Yushima or Todaimae stations. The final destination is the Bunkyo Ogai Mori Ogai Memorial Museum, located on a hill in Sendagi, where Ogai Mori built his own residence.

Ogai had a close relationship with Hongo, including Shinbunsha, where he studied German in Tokyo, the University of Tokyo, where he studied medicine, and the house called Kanchoro, where he lived for about 30 years.

For example, in “Geese,” Ogai begins his story with the words, “At that time, I was living in a boarding house called Kamijo, right across from the iron gate of the University of Tokyo, with the protagonist of this story living next to me, just one wall away. The story begins with the following sentence: “I lived in a boarding house called Kamijo, right across from the iron gate of the University of Tokyo. The geese appear as an important symbol in the story, and I would like readers to read it while thinking about the landscape of the area where geese used to live.

Even if we speak of writers in Hongo (or rather, I came to Nezu and Sendagi), there were rich people like Shoyo Tsubouchi and Ogai Mori, and there were also people who created works while living in poverty. The “ups and downs” of touring long distances at a stretch were quite challenging. This trip, where you experience the difference in elevation and distance as much as trekking, is enjoyable enough even if you only go to the places you want to visit in a short time. By the way, the Mori Ogai Memorial Museum has a café with a German-style menu that looks delicious.

Mori Ogai Memorial Hall, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

1-23-4 Sendagi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

03-3824-5511https://moriogai-kinenkan.jp/

Interview and text by Atsunori Takeda (steam)

Photo: Satoshi Okubo

Literary commentary: Yuma Watanabe