Walking around Edo with old mapsMarunouchi/YaesuNihonbashi (bridge)

Part 3: Once Edo’s Best Shopping Zone. Tracing the Traces of the Fish Market in Nihonbashi

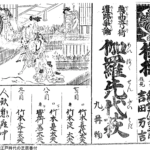

log bridgelaying on of hands and feet of Miura (during the Edo period)this corrupt or degenerate worldShrine of the Goddess of Mercyriverside fish market

Tokyo is a city that transforms itself in a year, a half year, or even a week. While new buildings are being constructed and new stores are opening, it is surprising to find traces of the old days, and that some things are actually “as they were in the Edo period.

The “Tokyo Old Map Walk” is a way to enjoy such evidence of the times based on old maps. Guided by Tae Hoshino, a guide from the pioneering “Walking Trip Ouensha,” we will walk through present-day Tokyo to discover Edo. This time, we will travel to the Nihonbashi fish market.

Nihonbashi Exit of Tokyo Station. The current map will soon become an old map⁉

The starting point is the “Nihonbashi Exit” of Tokyo Station. This is a rare exit that is not accessible from conventional lines, but only from the Shinkansen ticket gates. But because of this, it seems to have potential as a new gateway to Tokyo, and a new district called “TOKYO TORCH” with a 390-meter-high tower and a 7,000 ㎡ plaza is scheduled to be established in 2027. I departed with the impression that the current map will become a bit of an old map by doing so.

This time, we will walk along the Nihonbashi River, recalling the traces of the bustle of Edo’s best fish market.

Our starting point is the blank space in the lower left corner of the map. Let’s zoom in a little to get a better view.

The Nihonbashi River flows in the center of the map from left to right, and the outer moat intersects the left side of the map from north to south. The area south of the Nihonbashi River has been reclaimed and is now called Sotobori-dori. This time, let’s start from Isseki-bashi Bridge in the Nihonbashi area and take a tour of the traces of the Nihonbashi River and COREDO Muromachi, which was built after the river was reclaimed.

The “Ishi Ishibashi Lost Child Warning Stone Marker” reminds people of the bustle of the fish market.

First, we came across the “Isseki Bridge” at the place where the Nihonbashi River connects with the outer moat. The modern design of the main pillar is a remnant of a bridge built in 1922. The bridge itself is said to have existed since the early Edo period and was named after a prominent resident of the town.

Goto Shozaburo, a shogunate official in charge of money reform, lived at the north end, and Goto Uetonsuke, a draper for the shogunate, lived at the south end. Goto and Goto together, in other words, “Gotou(per)+It is said that the name “Itto” was derived from the Japanese word for “one stone” (+5to = one stone),” says Hoshino.

Incidentally, “ichito” refers to the one ton of sake in a one ton barrel, which can still be seen today at Kagamibiraki ceremonies and other events. The volume is 10 masu, or 18 liters. The Bank of Japan’s head office is located on the other side of the bridge, but it was built on the site of Shozaburo Goto’s gold-stand.

Furthermore, a “stone marker to warn lost children of the Ichisekibashi Bridge” stands quietly next to the magnificent main pillar.

It is a bulletin board for exchanging information on lost children. At that time, the number of lost children due to the crowds at the fish market was considered a problem, and this pillar was erected in the town. On the left side of the pole, parents of lost children put up a piece of paper describing the child’s characteristics, and on the right side, people who saw the child put up the location of the lost child.

Well, I guess that’s how crowded the place was. The Ichigokubashi Bridge is also known as “Yatsumi-no-Bashi” (Bridge of Eight Views) because it offers a view of eight bridges, including this bridge, Nihonbashi, Edobashi, and Tokiwa-bashi.

- In addition to being introduced as “Yatsumi Bridge” in “Edo Meisho Zue,” Utagawa Hiroshige also depicted it as “Yatsumi no Hashi” in his “Meisho Edo Hyakkei” (One hundred Famous Views of Edo), View No. 62.

Brick piers remain on the Nishigawashi Bridge built in the Meiji era.

This area is marked on an old map as “Nishikawagishi-machi. The origin of the name is exactly “west of the Nihonbashi fish market. In the Edo period (1603-1867), the next bridge after the Issekibashi Bridge was the Nihonbashi Bridge, but now the Nishigawagishi Bridge, which is derived from the old name of the area, has been built.

This bridge was built in 1891, but collapsed during the Great Kanto Earthquake, and was replaced by the current bridge in 1925. The bridge was restored and maintained in 1990, and at a glance, it looks like an ordinary bridge, but the bricks on the bridge piers remind us of the history of the bridge.

Mr. Hoshino pointed this way and saw an old stone wall on the “back” of the embankment. Remnants of the revetment that existed before the current concrete embankment can still be seen today.

- The thick concrete on the right side of the screen is the current revetment. The old revetment can be seen behind it.

Nihonbashi is well known for its many long-established stores. Eitaro Sohonsho,” famous for its “Meidai Kinsubaku” and “Kuroeya,” which has been supplying first-class lacquerware to the Imperial Household and the Imperial Household Agency, both stand side by side in the former Nishikawagishi-machi. Here are two anecdotes Mr. Hoshino shared with us.

Eitaro is well known for its Ume-boshi candy as well as Kintsuba, but it is said that around the Meiji and Taisho periods, Ume-boshi candy was popular among geiko and maiko because it was used as a base for rouge to give a nice shine to their lips without causing roughness.

Kuroeya has a giboshu, a decorative bead that dates back to the days when the Nihonbashi Bridge was made of wood (photo below / courtesy of Kuroeya). Giboshu are decorations attached to the pillars of bridges and stairways of temples and shrines. They were brought to Kuroeya after the war, when the store was burned down and the store was run from barracks. They are now displayed in a showcase in front of the store.

It is strange that the area has attracted a “part” of Nihonbashi, even though it has not been trading in antiques since the end of World War II.

In the Edo period, it was the starting point of the Five Routes. Nihonbashi” designated as a National Important Cultural Property.

And what you will soon see is the Nihonbashi Bridge.

The bridge was built in the early Edo period as part of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s town improvement efforts, and since then it has burned down more than a dozen times during the Edo period. The bridge was replaced by a Western-style flat bridge after the Meiji Restoration, and the current stone bridge was built in 1911. The current stone bridge was built in 1911. It is now designated as a National Important Cultural Property. This is the “Road Marker” for Japan and Tokyo.

National Routes 1 and 4 started from this place, which was the starting point of the Five Routes in the Edo period!

- This is the pillar representing the road marker. It used to be placed on the road, but now it is installed on the Metropolitan Expressway running above.

Even with this basic information, there is still much to be said about Nihonbashi.

First of all, the title “Nihonbashi” was written by Yoshinobu Tokugawa. It was originally written vertically. Mr. Hoshino says that the layout was changed to a horizontal position and the characters mounted on the wall of the Metropolitan Expressway were made into a relief.

- The character for “Nihonbashi” based on the handwriting of Yoshinobu Tokugawa. Originally written vertically

And it features bronze decorations with a majestic appearance. The kylin, lion, and decorative pillars, familiar from Keigo Higashino’s novels, are cool. The fact that such a Meiji-era design remains in the heart of Tokyo’s Chuo Ward is a surprise to begin with.

The decorative advisor, apart from designing the bridge, was one of the masters of Meiji architecture, Yorihiro Tsumaki.(in the middle of a sentence)was in charge of the project. While based on Western design, the design incorporates Eastern motifs and is actually full of originality.

Take the kylin, for example. The Qilin, for example, is an imaginary creature, of course, but it has a significant characteristic that the “real” one does not have.

It is the wings. It is said to be an image of flying from the starting point of Japan Road, and this is the motif of the dorsal fin of a fish. Perhaps it is connected to the fish market.

And the plants depicted on the pillars are pine trees and enoki(Enoki mushroom)The design incorporates the rows of pine trees along the Tokaido Highway starting at Nihonbashi and the enoki trees planted in the Edo period as markers for the Ichirizuka. The design incorporates the rows of pine trees along the Tokaido Highway starting at Nihonbashi and the enoki trees planted in the Edo period as markers for the Ichirizuka,” he said.

- I see, the wings of the kylin are fish-like. The plant around the center of the pillar is a pine tree, and the enoki below it is arranged. There is also a lion’s face at the top.

I zoomed in. Okay, so the plant in the center of the pillar is a pine tree, and below it is probably an enoki. I thought the Nihonbashi itself was very cool, but I had no idea about the dorsal fin, the pine tree, or the enoki!

And if you look closely, there is a lion carved on the top of the pillar. So here is the question. How many lions are there in Nihonbashi? The correct answer is – if you are going to the site, please count them – 34. If you only look on the bridge, you will never find them all.

Monument and statue of Otohime that tells the history of Nihonbashi Fish Market

The Nihonbashi Fish Market was bustling from Nihonbashi to the next Edobashi area along the Nihonbashi River. From the Edo period until the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12), Nihonbashi had a fish market. After the earthquake, the fish market was relocated to Tsukiji, and now it is further relocated to Toyosu Market. On the east side of the north side of the Nihonbashi Bridge, there is a monument “Birthplace of Nihonbashi Fish Market” and a plaza with a statue of Otohime-sama.

- A statue of Otohime-sama placed in the plaza of the former fish market in Nihonbashi. It looks a little like the symbol of that coffee shop that originated in Seattle.

In the past, a pier was built along the riverbank where unloaded fish and products from all over Japan were sold along the river. Today, there is no trace of the fish market at all, but beside Otohime-sama, there is a sign that tells of the bustle of the fish market in the Taisho period (1912-1926).

The fish market remained here until 1923, when it was relocated after the Great Kanto Earthquake and became Tsukiji Market. In a way, the Nihonbashi fish market is like the roots of Tokyo’s wholesale market.

Now, let’s stop by another famous historical site in Edo. The residence of Williams Adams, who drifted to Japan on a Dutch ship and was valued by Ieyasu for his knowledge of shipbuilding, navigation, and astronomy, was located in this area.

It is just one street north of the riverside street. In terms of the address, Anjin Miura received a house in what is now Nihonbashi-Honcho 1-chome, and this area was named Anjinmachi. In 1932, it was incorporated into Nihonbashi Muromachi 1-chome and Nihonbashi Honcho 1-chome, and the name of the town was lost, but the street where the mansion was located is called Anjinrin-dori.

To be honest, this is a small shopfront on a street that is not very wide. It is a small historic site that you can never visit if you don’t know about it, so why don’t you stop by and think about Edo?

The city with 300 years of history is still glamorous even today.

On the other hand, rather than “historic sites,” there are many long-established shops that have continued from the Edo period to the present. The north side of Nihonbashi, where Anjin Dori Street is also located, is a main street that once connected to the Nakasendo Road. Along with the development of the highway, merchants and merchant families were made to live along the street, creating a system for the development of the town.

With the vitality of Edo still intact, Nihonbashi is still bustling with people today.

Yamamoto Nori Store, for example, has been dedicated to the laver business since its establishment in Kaei 2. Not only does the store offer the finest laver products from around Japan, but visitors can also experience the history and culture of the laver trade.

And “Nimben,” founded in Genroku 12, offers not only traditional dried bonito flakes backed by over 300 years of history, but also fresh products and services that meet today’s needs. The company continues to offer new ways to enjoy its products and services.

While development is progressing and cutting-edge buildings are being built one after another in Nihonbashi, long-established stores that have existed since the Edo period still coexist, creating a new image of Nihonbashi. It is an image of a town where one can enjoy the atmosphere and sophistication of the Edo period without having to rely on old maps. However, the last place we were guided to on our old map walk was COREDO Muromachi. However, it was not inside the building, but in an alley.

Ukiyo Koji is located in Nihonbashi Muromachi 2-chome, passing between COREDO Muromachi 1 and YUITO ANNEX on Chuo Dori. The name is said to be “Ukiyo Shoji.

- Modern-day Ukisekoji is lined with fashionable stores on both sides of the alley.

In the Edo period (1603-1867), this was the residence of the Kitamura family, a town elder with roots in Kaga. In Kaga, the word for alley is “shoji,” so they called the alley beside the mansion that way.

As you can see, it is an alley, so to speak. But although it may not be exactly as it looks, it is clearly marked on an old map. Here it is.

And the “Fukutoku Shrine” on this old map still exists today.

It seems that this was originally a small shrine in the village. But there is a legend that Ieyasu visited the shrine and that the second shogun, Hidetada, gave it the alias “Meibuki Inari.” With the modernization of the area, the shrine was downsized and moved to various places in the neighborhood, but a new shrine was built beside “COREDO Muromachi” as the area was redeveloped.

Although the shrine is located in the middle of a valley of buildings (……), it is a place where people can see ladies in school uniforms, madams on their way to the store, men in suits, etc. all paying their respects to the shrine in a serious and ordinary manner.

In this fish market tour, there were no vestiges of the fish market in the first place, and the Nihonbashi area, which was the main attraction, has a modern Japanese appearance since the end of the Meiji period. Even in modern Tokyo, you can experience a part of the Edo lifestyle. Even in modern Tokyo, one can still experience a part of the Edo lifestyle.

Interview and text by Atsunori Takeda (Steam)

Photo by Satoshi Okubo

Supported by Walking Trip Ouensha

This time, a tour of the townOutline

| address (e.g. of house) | Kuroeya Kokubu Building, 1-2-6 Nihonbashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo |

|---|---|

| Access | 1 minute from Nihonbashi Station on the Tokyo Metro and Toei Subway lines, 3 minutes from Mitsukoshimae Station on the Tokyo Metro line, 8 minutes from Tokyo Station on the JR and Tokyo Metro lines |

| phone | 03-3272-0948 |

| External Links |